“Directed Thinking” involves asking people to think about information related to a topic that they already know which directs them to action. A study in the Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research shows how “directed thinking” led to an increase in exercise performance and fitness in sedentary college students.

Laura L. Ten Eyck, PhD, Dana P. Gresky, PhD, and Charles G. Lord, PhD, studied 61 college students who did not exercise on a regular basis or exercised inconsistently. Researchers asked students to think about ideas that fell into either the “reasons” category or the “actions” category. For example, some participants were asked to list the reasons why they should increase the performance of a target cardiovascular exercise they had previously selected, such as to be healthier or lose weight. Other participants were asked to list actions they could take to increase exercise performance, such a joining a gym or working out with a friend.

Having the students for eight weeks bring to mind and list actions they could take to increase exercise performance led to an increase in exercise and improved cardiovascular fitness. However, having students repeatedly bring to mind the reasons why they should do the target exercise did not increase time spent exercising.

“Our results suggest that people who are out of shape and at risk for serious health problems may be able to think their own way out of their unhealthy lifestyle and onto the path towards better physical fitness,” the authors conclude. “It could change the way that people think about motivating themselves and others.”

Journal reference:

- Laura L. Ten Eyck, Dana P. Gresky, Charles G. Lord. Effects of Directed Thinking on Exercise and Cardiovascular Fitness. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 2007; 12 (3-4): 237 DOI: 10.1111/j.1751-9861.2008.00023.x

Attention office workers, couch potatoes, and other sedentary people: reduce your time spent sitting by getting up and using your muscles more regularly throughout the day, says Dr. Genevieve N. Healy.

Breaks from sedentary activity appear to complement the health benefits gleaned from other types of physical activity. Moreover, Healy told Reuters Health, “a break could be as simple and light in intensity as standing and stretching.”

Healy, from the University of Queensland, in Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues measured the non-sleeping sedentary and active time of 168 Australian adults to determine whether taking breaks might impact their weight and metabolism. The subjects were participants in the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle study, but did not have diabetes.

This healthy group, who ranged in age from 30 to 87 years, kept an activity diary and wore an accelerometer during all waking hours for 7 days, the researchers report in Diabetes Care. The accelerometer, worn firmly around the trunk, measured the duration, type, and intensity of physical activity in counts per minute.

The researchers considered accelerometer counts of less than 100 per minute as sedentary periods, and counts of 100 or greater as active time. Light-intensity activity was from 100 to 1951 per minute and counts more than 1951 were periods of moderate-to-vigorous activity.

Overall, participants spent 57, 39, and 4 percent of their waking hours in sedentary, light-intensity, and moderate-to-vigorous intensity activity, respectively. On average, their breaks lasted less than 5 minutes, with accelerometer counts of 514 per minute.

They found that the number of breaks from sedentary activity positively correlated with lower waist circumference, lower triglycerides, and lower 2-plasma glucose scores.

Further studies should examine the physiological and metabolic responses in larger groups of people during prolonged periods of sitting and regular interruptions with short bouts of activity, Healy added.

http://prelive.news.com.au/story/0,23599,23516594-36398,00.html

Acupuncture helped alleviate lingering pain and decreased shoulder mobility in people who had surgery for head and neck cancer, according to U.S. researchers at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago. This therapy also resulted in significant improvements in extreme dry mouth or xerostomia, which often occurs in people who have had radiation treatment for head and neck cancer.

Researchers at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York studied 70 patients who were at least three months past their surgery and radiation treatments.About half got standard treatments, which include physical therapy and treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs. The other half got standard treatment plus a weekly acupuncture session.

After four weeks, 39 percent of those who got acupuncture reported improvements in pain and mobility, compared with only 7 percent in people who got typical care.

“Although further study is needed, these data support the potential role of acupuncture in addressing post neck-dissection pain and dysfunction, as well as xerostomia,” Memorial Sloan-Kettering’s Dr. David Pfister said at the meeting.

New data from a randomized, controlled trial found that acupuncture provided significant reductions in pain, dysfunction, and dry mouth in head and neck cancer patients after neck dissection. The study was led by David Pfister, MD, Chief of the Head and Neck Medical Oncology Service, and Barrie Cassileth, PhD, Chief of the Integrative Medicine Service, at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). Dr. Pfister presented the findings May 30 at the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology.

Neck dissection is a common procedure for treatment of head and neck cancer. There are different types of neck dissection, which vary based on which structures are removed and the anticipated side effects. One type — the radical neck dissection — involves complete removal of lymph nodes from one side of the neck, the muscle that helps turn the head, a major vein, and a nerve that is critical to full range of motion for the arm and shoulder.

“Chronic pain and shoulder mobility problems are common after such surgery, adversely affecting quality of life as well as employability for certain occupations,” said Dr. Pfister. Nerve-sparing and other modified radical techniques that preserve certain structures without compromising disease control reduce the incidence of these problems but do not eliminate them entirely. Dr. Pfister adds, “Unfortunately, available conventional methods of treatment for pain and dysfunction following neck surgery often have limited benefits, leaving much room for improvement.”

Seventy patients participated in the study and were randomized to receive either acupuncture or usual care, which includes recommendations of physical therapy exercises and the use of anti-inflammatory drugs. For all of the patients, at least three months had elapsed since their surgery and radiation treatments. The treatment group received four sessions of acupuncture over the course of approximately four weeks. Both groups were evaluated using the Constant-Murley scale, a composite measure of pain, function, and activities of daily living.

Pain and mobility improved in 39 percent of the patients receiving acupuncture, compared to a 7 percent improvement in the group that received usual care. An added benefit of acupuncture was significant reduction of reported xerostomia, or extreme dry mouth. This distressing problem, common among cancer patients following radiotherapy in the head and neck, is addressed with only limited success by mainstream means.

“Like any other treatment, acupuncture does not work for everyone, but it can be extraordinarily helpful for many,” said Dr. Cassileth. “It does not treat illness, but acupuncture can control a number of distressing symptoms, such as shortness of breath, anxiety and depression, chronic fatigue, pain, neuropathy, and osteoarthritis.”

“Cancer patients should use acupuncturists who are certified by the national agency, NCCAOM [National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine], and who are trained, or at least experienced, in working with the special symptoms and problems caused by cancer and cancer treatment,” she added.

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (2008, May 31). Acupuncture Reduces Pain And Dysfunction In Head And Neck Cancer Patients

Fruits and vegetables contain essential vitamins, minerals and fiber that are key to good health. Now, a newly released study by Agricultural Research Service (ARS)-funded scientists suggests plant foods also may help preserve muscle mass in older men and women.

The study was led by physician and nutrition specialist Bess Dawson-Hughes at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University in Boston, Mass.

The typical American diet is rich in protein, cereal grains and other acid-producing foods. In general, such diets generate tiny amounts of acid each day. With aging, a mild but slowly increasing metabolic “acidosis” develops, according to the researchers.

Acidosis appears to trigger a muscle-wasting response. So the researchers looked at links between measures of lean body mass and diets relatively high in potassium-rich, alkaline-residue producing fruits and vegetables. Such diets could help neutralize acidosis. Foods can be considered alkaline or acidic based on the residues they produce in the body, rather than whether they are alkaline or acidic themselves. For example, acidic grapefruits are metabolized to alkaline residues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis on a subset of nearly 400 male and female volunteers aged 65 or older who had completed a three-year osteoporosis intervention trial. The volunteers’ physical activity, height and weight, and percentage of lean body mass were measured at the start of the study and at three years. Their urinary potassium was measured at the start of the study, and their dietary data was collected at 18 months.

Based on regression models, volunteers whose diets were rich in potassium could expect to have 3.6 more pounds of lean tissue mass than volunteers with half the higher potassium intake. That almost offsets the 4.4 pounds of lean tissue that is typically lost in a decade in healthy men and women aged 65 and above, according to authors.

Sarcopenia, or loss of muscle mass, can lead to falls due to weakened leg muscles. The authors encourage future studies that look into the effects of increasing overall intake of foods that metabolize to alkaline residues on muscle mass and functionality.

The study was published in the March issue of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

US Department of Agriculture (2008, May 31). Plant Foods For Preserving Muscle Mass.

The push-up is the ultimate barometer of fitness. It tests the whole body, engaging muscle groups in the arms, chest, abdomen, hips and legs. It requires the body to be taut like a plank with toes and palms on the floor. The act of lifting and lowering one’s entire weight is taxing even for the very fit.

“You are just using your own body and your body’s weight,” said Steven G. Estes, a physical education professor and dean of the college of professional studies at Missouri Western State University. “If you’re going to demonstrate any kind of physical strength and power, that’s the easiest, simplest, fastest way to do it.”

But many people simply can’t do push-ups. Health and fitness experts, including the American College of Sports Medicine, have urged more focus on upper-body fitness. The aerobics movement has emphasized cardiovascular fitness but has also shifted attention from strength training exercises.

Moreover, as the nation gains weight, arms are buckling under the extra load of our own bodies. And as budgets shrink, public schools often do not offer physical education classes — and the calisthenics that were once a childhood staple.

In a 2001 study, researchers at East Carolina University administered push-up tests to about 70 students ages 10 to 13. Almost half the boys and three-quarters of the girls didn’t pass.

Push-ups are important for older people, too. The ability to do them more than once and with proper form is an important indicator of the capacity to withstand the rigors of aging.

Researchers who study the biomechanics of aging, for instance, note that push-ups can provide the strength and muscle memory to reach out and break a fall. When people fall forward, they typically reach out to catch themselves, ending in a move that mimics the push-up. The hands hit the ground, the wrists and arms absorb much of the impact, and the elbows bend slightly to reduce the force.

In studies of falling, researchers have shown that the wrist alone is subjected to an impact force equal to about one body weight, says James Ashton-Miller, director of the biomechanics research laboratory at the University of Michigan.

“What so many people really need to do is develop enough strength so they can break a fall safely without hitting their head on the ground,” Dr. Ashton-Miller said. “If you can’t do a single push-up, it’s going to be difficult to resist that kind of loading on your wrists in a fall.” And people who can’t do a push-up may not be able to help themselves up if they do fall. “To get up, you’ve got to have upper-body strength,” said Peter M. McGinnis, professor of kinesiology at State University of New York College at Cortland who consults on pole-vaulting biomechanics for U.S.A. Track and Field, the national governing body for track.

Natural aging causes nerves to die off and muscles to weaken. People lose as much as 30 percent of their strength between 20 and 70. But regular exercise enlarges muscle fibers and can stave off the decline by increasing the strength of the muscle you have left.

Women are at a particular disadvantage because they start off with about 20 percent less muscle than men. Many women bend their knees to lower the amount of weight they must support. And while anybody can do a push-up, the exercise has typically been part of the male fitness culture. “It’s sort of a gender-specific symbol of vitality,” said R. Scott Kretchmar, a professor of exercise and sports science at Penn State. “I don’t see women saying: ‘I’m in good health. Watch me drop down and do some push-ups.’ ”

Based on national averages, a 40-year-old woman should be able to do 16 push-ups and a man the same age should be able to do 27. By the age of 60, those numbers drop to 17 for men and 6 for women. Those numbers are just slightly less than what is required of Army soldiers who are subjected to regular push-up tests.

If the floor-based push-up is too difficult, start by leaning against a countertop at a 45-degree angle and pressing up and down. Eventually move to stairs and then the floor.

Acupuncture and myofascial trigger points therapy each focus on hundreds of similar points on the body to treat pain, although they do it differently, says a physician at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville who analyzed the two techniques.

Acupuncture and myofascial trigger points therapy each focus on hundreds of similar points on the body to treat pain, although they do it differently, says a physician at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville who analyzed the two techniques.

Results of the study, published May 10 in the Journal of Complementary and Alternative Medicine, suggest that people who want relief from chronic musculoskeletal pain may benefit from either therapy, says chronic pain specialist Dr. Peter Dorsher of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Mayo Clinic.

“This may come as a surprise to those who perform the two different techniques, because the notion has been that these are exclusive therapies separated by thousands of years,” he says. “But this study shows that in the treatment of pain disorders, acupuncture and myofascial techniques are fundamentally similar – and this is good news for anyone looking for relief.”

Classic Chinese acupuncture treats pain and a variety of health disorders using fine needles to “reset” nerve transmission, Dorsher says. Needles are inserted in one or several of 361 classical acupoints to target specific organs or pain problems. “This is a very safe and effective technique,” he says.

Myofascial trigger-point therapy, which has evolved since the mid-1800s, focuses on tender muscle or “trigger point” regions. There are about 255 such regions described by the Trigger Point Manual, the seminal textbook on myofascial pain. These are believed to be sensitive and painful areas of muscle and fascia, the web of soft tissue that surrounds muscle, bones, organs and other body structures. To relieve pain at these trigger points, practitioners use injections, deep pressure, massage, mechanical vibration, electrical stimulation and stretching, among other techniques.

In the study, Dorsher analyzed studies published on both techniques and demonstrated that acupuncture points and trigger points are anatomically and clinically similar in their uses for treatment of pain disorders.

In another recent study, he found that at least 92 percent of common trigger points anatomically corresponded with acupoints, and that their clinical correspondence in treating pain was more than 95 percent. “That means that the classical acupoint was in the same body region as the trigger point, was used for the same type of pain problem, and the trigger point referred pain pattern followed the meridian pathway of that acupoint described by the Chinese more than 2,000 years before,” Dorsher says. Myofascial pain therapy has lately incorporated the use of acupuncture needles in a treatment called “dry needling” to treat muscle trigger points.

“I think it is fair to say that the myofascial pain tradition represents an independent rediscovery of the healing principles of traditional Chinese medicine,” Dorsher says. “What likely unites these two disciplines is the nervous system, which transmits pain.”

Mayo Clinic (2008, May 14). Acupuncture And Myofascial Trigger Therapy Treat Same Pain

Podiatrist Emily Splichal talks about posture and stiletto.

According to Mayo Clinic these are the conditions that can be casued by wearing high heels shoes:

- Corns and calluses. Thick, hardened layers of skin develop in areas of friction between your shoe and your foot. Painful rubbing can occur from wearing a high heel that slides your foot forward in your shoe or from a too-narrow toe box that creates uncomfortable pressure points on your foot.

- Toenail problems. Constant pressure on your toes and nail beds from being forced against the front of your shoe by a high heel can lead to nail fungus and ingrown toenails.

- Hammertoe. When your toes are forced against the front of your shoe, an unnatural bending of your toes results. This can lead to hammertoe — a deformity in which the toe curls at the middle joint. Your toes may press against the top of the toe box of your shoe, causing pain and pressure.

- Bunions. Tightfitting shoes may worsen bunions — bony bumps that form on the joint at the base of your big toe. Bunions can also occur on the joint of your little toe (bunionettes). Experts disagree on whether tightfitting, pointy-toed, high-heeled shoes cause bunions or bunionettes, but such shoes can exacerbate an already existing problem.

- Tight heel cords. If you wear high heels all the time, you risk tightening and shortening your Achilles tendon — the strong, fibrous cord that connects your calf muscle to your heel bone. Your Achilles tendon helps you point your foot downward, rise on your toes and push off as you walk. Wearing high heels prevents your heel bones from regularly coming in contact with the ground, which in turn keeps your Achilles tendon from fully stretching. Over time, your Achilles tendons contract to the point that you no longer feel comfortable wearing flat shoes.

- Pump bump. Also known as Haglund’s deformity, this bony enlargement on the back of your heel can become aggravated by the rigid backs or straps of high heels. Redness, pain and inflammation of the soft tissues surrounding the pump bump result. Heredity may play a role in developing Haglund’s deformity, but wearing high heels can worsen the condition.

- Neuromas. A growth of nerve tissue — known as Morton’s neuroma or plantar neuroma — can occur in your foot, most commonly between your third and fourth toes, as a result of wearing tightfitting shoes. A neuroma causes sharp, burning pain in the ball of your foot accompanied by stinging or numbness in your toes.

- Joint pain in the ball of the foot (metatarsalgia). High heels cause you to shift more weight to the ball of your foot, rather than distributing your weight over the entire foot. This causes increased pressure, strain and pain in your forefoot. Shoes with tightfitting toe boxes can lead to similar discomfort.

- Stress fractures. Tiny cracks in one of the bones of your foot — stress fractures — may result from the pressure high heels place on your forefoot.

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/foot-problems/WO00114

For the first time researchers are beginning to understand exactly how various forms of exercise impact the heart. Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators, in collaboration with the Harvard University Health Services, have found that 90 days of vigorous athletic training produces significant changes in cardiac structure and function and that the type of change varies with the type of exercise performed.

“Most of what we know about cardiac changes in athletes and other physically active people comes from ’snapshots,’ taken at one specific point in time. What we did in this first-of-a-kind study was to follow athletes over several months to determine how the training process actually causes change to occur,” says Aaron Baggish, MD, a fellow in the MGH Cardiology Division and lead author of the study.

To investigate how exercise affects the heart over time, the MGH researchers enrolled two groups of Harvard University student athletes at the beginning of the fall 2006 semester. One group was comprised of endurance athletes — 20 male and 20 female rowers — and the other, strength athletes — 35 male football players. Student athletes were studied while participating their normal team training, with emphasis on how the heart adapts to a typical season of competitive athletics.

Echocardiography studies — ultrasound examination of the heart’s structure and function — were taken at the beginning and end of the 90-day study period. Participants followed the normal training regimens developed by their coaches and trainers, and weekly training activity was recorded. Endurance training included one- to three-hour sessions of on-water practice or use of indoor rowing equipment. The strength athletes took part in skill-focused drills, exercises designed to improve muscle strength and reaction time, and supervised weight training. Participants also were questioned confidentially about the use of steroids, and any who reported such use were excluded from the study.

At the end of the 90-day study period, both groups had significant overall increases in the size of their hearts. For endurance athletes, the left and right ventricles — the chambers that send blood into the aorta and to the lungs, respectively — expanded. In contrast, the heart muscle of the strength athletes tended to thicken, a phenomenon that appeared to be confined to the left ventricle. The most significant functional differences related to the relaxation of the heart muscle between beats — which increased in the endurance athletes but decreased in strength athletes, while still remaining within normal ranges.

“We were quite surprised by both the magnitude of changes over a relatively short period and by how great the differences were between the two groups of athletes,” Baggish says. “The functional differences raise questions about the potential impact of long-term training, which should be followed up in future studies.”

While this study looks at young athletes with healthy hearts, the information it provides may someday benefit heart disease patients. “The take-home message is that, just as not all heart disease is equal, not all exercise prescriptions are equal,” Baggish explains. “This should start us thinking about whether we should tailor the type of exercise patients should do to their specific type of heart disease. The concept will need to be studied in heart disease patients before we can make any definitive recommendations.”

Their study appears in the April Journal of Applied Physiology. Baggish and senior author Malissa J. Wood, MD, of MGH Cardiology note that collaboration with the Harvard University Medical Services, led by Francis Wang, MD, was instrumental in the success of this study. Additional co-authors of the report are Rory Weiner, MD, Jason Elinoff, Francois Tournoux, Michael Picard, MD, and Adolph Hutter, MD, MGH Cardiology; and Arthur Boland, MD, Harvard University Health Services.

Massachusetts General Hospital (2008, April 23). How Exercise Changes Structure And Function Of Heart.

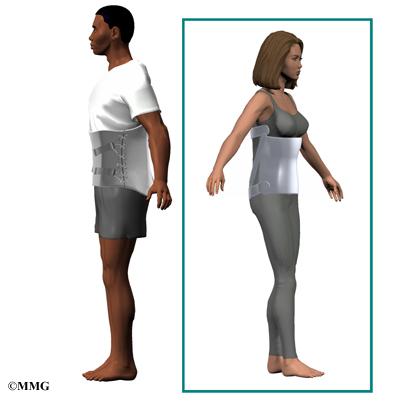

Lumbar or lower back supports — those large belts that people wear around their waists when they lift or carry heavy objects — are not very useful for preventing low back pain, according to a new systematic review.

Lumbar or lower back supports — those large belts that people wear around their waists when they lift or carry heavy objects — are not very useful for preventing low back pain, according to a new systematic review.

Although many people use lumbar supports to bolster the back muscles, they are no more effective than lifting education — or no treatment whatsoever — in preventing related pain or reducing disability in those who suffer from the condition, reviewers found.

“We recommend the general population and workers not wear lumbar supports to prevent low back pain or for the management of lower back pain,” said lead author Ingrid van Duijvenbode, a teacher and member of the research group at the Amsterdam School for Health Professionals in the Netherlands.

She and her colleagues looked at 15 studies — seven prevention and eight treatment studies — that included more than 15,000 people. When measuring pain prevention or reduction in number of sick days used, the researchers found little or no difference between people who used supports and their peers who did not.

“There is moderate evidence that lumbar supports do not prevent low back pain or sick leave more effectively than no intervention or education on lifting techniques in preventing long-term low back pain,” van Duijvenbode said. “There is conflicting evidence on the effectiveness of lumbar supports as treatment compared to no intervention or other interventions.”

The review appears in the latest issue of The Cochrane Library, a publication of The Cochrane Collaboration, an international organization that evaluates medical research. Systematic reviews draw evidence-based conclusions about medical practice after considering both the content and quality of existing medical trials on a topic.

“This continues the line of research that shows lumbar supports make no difference in treating or preventing low back pain,” said Joel Press, M.D., associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. “Looking at the literature on lumbar supports, it is difficult to make any conclusions because these studies are using supports for many different causes of low back pain. It would be hard to prove any one treatment is effective for every type of back pain, just as it would be difficult to prove that any one heart medication would be good for every type of heart problem.”

Press said that lumbar supports are useful only as an additional treatment to exercise and other interventions. He said that the bracing makes it more comfortable for some people to move around.

“I usually tell my patients asking about lumbar supports that while there is not a lot of evidence that it is useful overall, there are still individuals who might benefit from their use,” Press said. “But it should be used as an adjunct treatment if it helps to activate patients to increase their activity and exercise.”

Reference: van Duijvenbode ICD, et al. “Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low back pain (Review).” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2.

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/04/080422202813.htm